Visual Translation / Jump Cut: Donata Minderytė

When we were newborns, we instinctively knew how to read smiles and kisses, we could recognise worry wrinkles, bright colours, and different shapes. And that was enough for us. Later, the faces we had seen were replaced by names, and objects by lengthy terms. Language bestowed upon us, say, like a jump cut in a film or literary narrative, disrupting a long, slow progression, creating momentum, and swiftly jumping from one scene to the next. If life really is like cinema, why do editors decide to throw us out of the divine silence and into languages that often fail to facilitate communication anyway? Thus, we jumped from images to words, and started using words to interpret images. This text also undertakes to do so, even if its different parts keep jumping, much like the exhibition it describes: leaping across time, space, and an entire ocean (the works were created between Vilnius and New York), between thought and painting, between everyday life and PhD research.

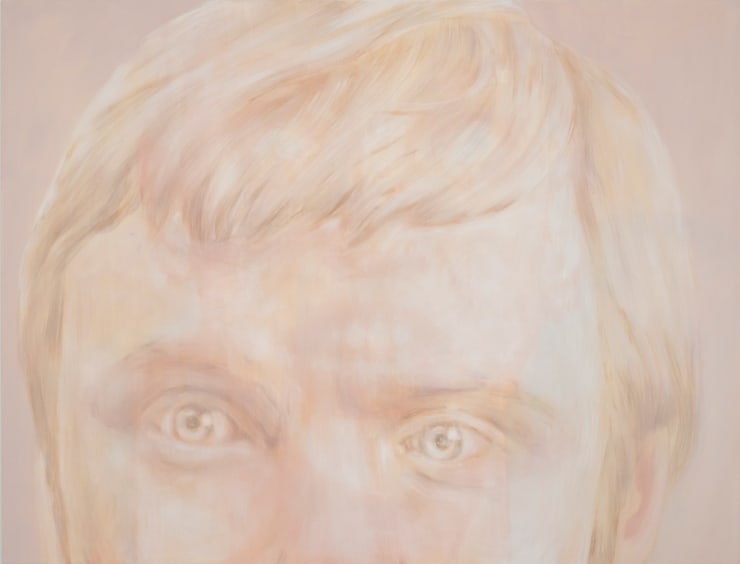

In the exhibition, the painter Donata Minderytė tests the potential of image translation, when images are wordlessly translated into other images, reverting them to their pre-verbal state and prompting an unlearning of all familiar stories, meanings, and connotations. Such translation can be seen as a jump – into another form of image, environment, and scale. The ‘native’ language of cinema, photographs, or personal videos is transformed into a distinctive proto-language of painting, where mundane, seemingly ordinary, or stop-motion shots speak an entirely different alphabet. Thus, the images before you – swaddled in canvases – are like children – ones yet (or already) incapable of speech. They are bizarre creations born from the tension and love between pixels and film, smooth brushstrokes and digital screens.

By peeling off the toughest shell of the image – its cultural context – Minderytė exposes its pulp, its very viscera, where the limitations of painting and the ambiguity of the image’s truthfulness lie dormant. What is more real here – a glimpse of fragmented reality, archives of captured images, or a face painted down to the tiniest pores? Could spending more time with the images make them more real? If so, this visual translation does not convey the same message: instead, it deceives, assembling the strangest chimaeras from the number of viewers’ gazes, memories, traces of meaning, and the echo of the image. Perhaps that is why the paintings here appear as if emptied out by scrutinising eyes, aged, faded by harsh light, or washed in titanium white. Others, in turn, remain somewhat untranslatable, singing loudly in Prussian blue.

Emphasising the possible fallacies of translation and the intentional mistakes in visual language, the painter constructs collages of quotations from films and life. Like a meticulous editor, Minderytė places these borrowed scenes in centre, leaving the tacit, bracketed, less important narrative aside. A jump cut occurs and she leaps into a completely different time and space, juxtaposing storylines and thus highlighting their anachronisms. Here lie gradually thickening tears and wounds, alongside seemingly unpainterly, zoomed-in countenances of her friends and herself. By capturing the gestures, choreography, and fragmented bodies of her generation, the artist gives life itself the significance of cinema. In other works, layers accumulate like palimpsests, with new images painted over old ones, reminiscent of simultaneous translation. This only goes to prove that stories and languages aren’t fixed, and that painting can transform our perception of time, the folds of the previous image, and the new connections born in leaps and jumps.

These cinematic excerpts, the painterly translations and journeys, along with the fascination with faces and gazes, seem to align with the sensitivity of contemporary art, recently identified by Artnet’s editor Kate Brown as hypersentimentalism. These gestures, depicting friends, community members, and loved ones on canvas, offer a respite from digital noise, political polemics, and the hustle of everyday life. Painting, as a medium, is still able to express care, tenderness, and empathy. In this case, the prefix hyper (from the Ancient Greek ὑπέρ – ‘beyond, over’) begins to mean not only something ‘excessive’, but also hints to hidden information.

This is how Minderytė’s exhibition, imbued with light nostalgia and longing for a happy ending of life as in a film, sounds in words; however, as we are well-aware, translation is merely a negotiation – between what has been said and what language still lacks in equivalents.

Text by Jogintė Bučinskaitė

Edited and translated by Alexandra Bondarev

The exhibition is partly funded by: Vilniaus City Municipality

Patrons: Renata ir Rolandas Valiūnai

Gallery supported by: Vilniaus City Municipality, Lietuvos Rytas, Vilma Dagilienė, Romas Kinka, Ekskomisarų biuras, MailerLite, Plieno Spektras, Vyno klubas

Graphic design: Taktika studio